This

above quote is taken from Kay Larson’s book ‘Where the Heart Beats – John Cage,

Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists’ and refers to the kind of sudden illumination

that unfortunately has become quite rare in Western civilization – or at least

is never recognized anymore. This could be because these flashes are indeed

quite rare in anyone’s life, as they only seem to happen a few times – if that.

I experienced two of these moments a couple of years ago, one shortly after the

other. The first one was the morning I decided to take LSD for the first time,

an experience that would radically alter my whole outlook on life. But the

funny thing was, it had already begun to change immediately after I had taken

the drug but before its effect had begun to manifest itself. Shortly after

putting the little piece of paper under my tongue I was somewhat aimlessly

surfing on the internet, perhaps as a way to take my mind off my considerable

nervousness as I wasn’t quite sure what to expect. But when doing so, I

suddenly read that Ingmar Bergman had passed away that day (since then I’d like

to think that Bergman died the day I had my spiritual rebirth as there’s more

than a little poetic logic in that). But even more astonishing was that a week

before I had decided, with some friends, to go see Bergman’s ‘Skammen’ in the

theater that very same night. Seeing

a Bergman picture in theaters was in itself not something I did every day, but

doing so on the very same day the man died, was too much to be ‘just’

coincidence – although modern Western civilization will call it just that. Of

course, this sudden bolt of realization that all things are connected preceded

the proper LSD experience itself, so curiously my whole outlook on life had

already began to change even before it technically could have.

Within

the space of about four months, my whole life turned upside down after this: I

quit my heavy drinking and ecstasy use from one day to the next, had the

courage to finally drop out of the University and started living my life according

to some radically different principles. And, most beautifully of all, it was

also during this time I met my current boyfriend. We met online (yes, such

encounters can lead to life-changing things), but we both never thought it would

go any further than one pleasant evening. It was with this in mind anyway that

I undertook the sizable voyage to his house, but when I rang the doorbell and

he opened the door… I became ionized once again. I can’t explain the feeling to

this day, except that I knew then and there this boy would be mine. Part of it

is the old cliché of love at first sight probably, but there was something more

to it than that. Call it Karma or whatever you will, but to me it was quite

literally the ultimate manifestation of all the changes I had been going

through these few months. Because it was again much too much of just a

coincidence to first have made myself complete (or at least was shown the path

to wholeness that I’ve since walked with my boyfriend), before finding my soul

mate, making my life complete. Obviously I can’t give any evidence for this

that’s even remotely scientific and since this is the only evidence most people

can understand nowadays, this whole story is bound to fall on deaf ears – which has in any case been the general

reaction of those around me. Since my transformation I’ve found it quite hard

to truly communicate with people (besides my boyfriend, with whom I have an

almost telepathic relationship) and I’m often struck by the feeling that works

of art speak more to me than most human beings. Which brings us to the truly

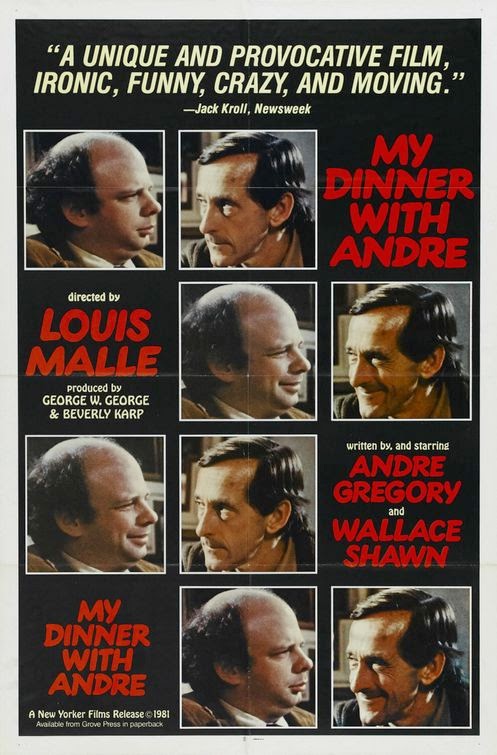

amazing experience I had with Louis Malle’s ‘My Dinner With Andre’, yet another

one of those rare moments of ionization.

In this

quaint little picture, while having dinner with playwright Wally (which makes

up the entire story), theater director Andre tells about a curious, somewhat

too coincidental moment when he stumbled upon a surrealist magazine with the

letters A in them, made the very same day he was born. The sudden burst of

illumination Andre felt was not only very similar to my own moments of

ionization, I also had the same kind of experience with this picture as a

whole, incidentally made in the very same the year I was born. Watching it was

without a doubt one of the most frightening and exhilarating moments of our (my

boyfriend’s and me) life. Because you see, I just ‘happened’ to have had an

encounter that was exactly the same as the one in the movie. Not similar, no – exactly

the same. I wonder if people can understand how this feels, I wonder if I have

ever felt it before. Clearly some kind of identification with a work of art is

not only possible, it’s arguably the basis for virtually all people while

watching a dramatic work of art. Everybody has to project his own feelings upon

movie characters or have at least some part of the situation or emotions of a

character projected onto him. For instance, Carl Dreyer’s ‘Gertrud’ (1964) is

one of my favorite films as I can sympathize so strongly with the character of

Gertrud: her absolute refusal to compromise the purity of her vision can easily

be interpreted by people as plain stubbornness or lack of social skills (as I

unfortunately know all too well from experience). But even as she dies a lone

hermit at the end of the movie, Dreyer doesn’t present this as a failure, as

common sense would have it, but indeed as a triumph – something that I can

identify so strongly with I can almost taste it. But despite these incredibly

vivid feelings the movie evokes in me, as it represents something I believe in

so much – that’s not what I’m getting at here. It’s something much more than mere

projection, it’s like seeing a scene from your own life enacted on the big

screen, as I cannot emphasize enough how the entire movie ‘My Dinner With

Andre’ was not similar to my own experience but virtually identical. How fortunate

then for me, that one of the central themes running through the movie is how

art and life can intersect and imitate! But let me give you a broad sketch of

the particular evening of my life that’s so magnificently portrayed in the film

– with only some of the little details being a bit different.

Like

Andre, I had dinner with a friend I hadn’t seen for a very long time, although

in my case it was not in a restaurant but in my own home and with two old

friends instead of one, with also my boyfriend and one of their girlfriends

present. Like Wally, they asked me what had happened to me during the

intervening years, so, like Andre, I started talking about my encounters with

soul and spirituality that has so deeply informed all the other pieces on this

blog. At first, things were innocent enough with them just not really

understanding what I was getting at, like Wally. Everything Andre said could’ve

been a transcription of all the things I said that evening – although without

the eloquence perhaps. The one crucial difference between the movie and my life

was that, unfortunately, my discussion partners weren’t blessed with the

intelligence and patience of Wally. Not that they were stupid, far from it, but

our evening ended a complete disaster as especially my friend’s girlfriend got

so defensive and angry at everything I said she eventually broke down in tears

and totally upset stormed out the door. Sometimes you do wish you could live in

a movie.

In any

case, what both discussions of movie and my life have in common is the clash

between what Bill Plotkin calls egocentric and soulcentric ways of life, with

Wally representing the egocentric and Andre the soulcentric vision. As Wally’s

position is unfortunately the norm in our Western civilization, let me try to

explain Andre’s (and thus my own) a bit. From all the evidence the film gives

us, it’s clear he has been just going

through the developmental stage of life Plotkin calls the ‘Cocoon’. Now in

ideal soulcentric environments, the Cocoon occurs somewhere in the early

twenties, but as most of us live in an egocentric world, many people enter the

Cocoon much later (if at all) as is the case with Andre. It also directly

explains why Andre has been feeling somewhat uneasy about all this, as he now

feels mostly emptiness because he now realized his whole life has been a

charade. In better circumstances though (as, luckily, in my case) people enter

the Cocoon much earlier, which is to say: at the moment they have completed

their first, improvisatory social identity. This identity is usually formed

when someone is in his late teens and this is also where the rub is, as most

people in egocentric societies snugly fit themselves into that role the rest of

their lives, thinking it’s the end of their development when it really should

be only the beginning. Of course this begs the question somewhat as to why

someone would want to go to all the trouble of first forming a stable social identity

(a process that lasts twenty years) only to jettison that again the minute it

has formed? Well, this is a difficult question to answer, especially in

egocentric society where the prevalent idea seems to be, that life in general

is already so much trouble anyway, that one should try to make it easier

instead of harder. Which would make sense probably were it not for the fact

that the harder way is often the most lasting and valuable even if it’s not

always the easiest.

But let

me drag out my old friend LSD again. The experience of LSD is difficult to

describe, but is generally thought of as being a huge intensification of the

senses and the temporary obliteration of the Ego. In short, it is just another

way of looking at the same world and this is exactly where its value lies: the

way you experience the world on LSD is not better than our default mode, just different.

And it is this difference that makes all the difference, because now you don’t

have just one way of looking at the world, but suddenly you’ve got two and they

don’t contradict but complement each other. It’s little more than having two

different ways of looking at the same thing, which is always, without

exception, better than just one viewpoint. Say you hear that two mutual friends

of yours had a fight together and one of them tells you his side of the story.

With only this information you may very well think the behavior of the other

friend odd, until the next night, he

tells you what happened. Now at this point you are much better equipped to

judge what has transpired accurately as you suddenly have two sides of the same

story, which necessarily changes your whole relationship to said story. So it

is with life too. The first forming of a social identity in adolescence is

absolutely essential, but far from the end of the line. It is essential because

you need this stability as a starting point, but it’s also just the beginning

of your development as then you can utterly destroy everything you’ve build,

only to start building a new life on the ashes of your former identity. And not

only is this transformation (hence the name of the Cocoon) more complete

because you have both your old ways of looking and thinking as your new one. If

you do it right you can also start building it on your Soul instead of your Ego

as access to the Soul only becomes truly available again at that point (all

babies are in direct contact with Soul as Ego only begins to form around the

age of five). So the basis of your new identity can now be rooted in

authenticity instead of mere social acceptance. This may all sound very well to

some, but it does leave the question of why one should try to leave behind

familiarity and safeness in order to embark on this adventurous journey

somewhat unanswered, mainly because trying to explain it is similar to trying

to explain sex to someone who’s never experienced it – quite impossible. It is

fact one of the ultimate conundrums of life: much too often you only know why

you have to do certain things only after you’ve done them. Bill Plotkin calls

it marching directly into the fire, as repeatedly and unconditionally as one

can:

“What

you can be fairly certain of is that the fire will change you, although not in

a way you can accurately predict. Venturing into these unknown precincts,

you’ll have experiences that might be ecstatic or harrowing and painful, or

both, but either way they’re likely to alter you at your core, to reshape what you

know as the world, and to provide you with psychological and spiritual

opportunities you wouldn’t have had otherwise. Emerging on the other side of

that wall of flame, you might find yourself standing before a mysterious and

ominous door and choose to walk through, leading to a series of additional

thresholds that could in time afford an encounter with the mysteries of your

destiny”.

Alas, as

‘My Dinner With Andre’ (and my own life) makes all too perfectly clear,

developing yourself soulcentrically in an egocentric society is far from easy.

Because next to the considerable obstacles you already will find on your way to

spiritual enlightenment, you’ll also have to deal with those who don’t develop

in such a way and who will perceive your path as a threat, either consciously

or unconsciously. Consequently, one of the greatest challenges is the

fundamental difference in outlook and the lack of true communication this

creates. In my piece on Teacher’s Pet I’ve already spoken at length about

the crucial, if often overlooked difference between merely intellectual

understanding and a synthesis between understanding and feeling. ‘My Dinner

With Andre’ serves as a perfect illustration: at first, Wally is still able to

talk with Andre and they seem to agree on the general emptiness of most people

living in modern societies now and how theater has become superfluous as most

people do nothing more than perform all their lives. Wally is able to grasp

this concept on an intellectual basis but can’t see the larger implication of

all this, very probably because he himself is so much entangled in exactly such

a life. Besides understanding this concept intellectually, he also has feelings

about this topic, as becomes clear when he complains how he’s always confused

at a party and always feel uncomfortable. So he both understands and feels about it, but the two don’t

meet anywhere, which is because his feelings of inferiority are clearly rooted

in the small Ego instead of the large viewpoint of the Soul. Andre on the other

hand, because he is direct contact with Soul, is able to see the situation not

merely as some intellectual concept furnished with some petty feelings, but to

actually perceive the situation clearly for what it is. So when he talks about

a Scandinavian friend who he has known for years, but suddenly can’t stand his

pompousness, it’s not because he has become intolerant, but because he stands

both inside and outside society at the same time and thus has the ability to

see people in a certain light, that those who have been living in their egos

can’t even begin to fathom. So what he is complaining about is not just the

general lack of depth in contemporary society most people can agree on, but is

in actuality a life led without the depth of Soul and the Mysteries of the

universe.

Because

Andre knows both the position of Wally (because he has lived it almost all his

life) and his own current position, he has the vantage point of two different

viewpoints to Wally’s just one, which immediately makes the whole conversation

fraught with problems. How deep these problems are becomes painfully obvious

when Wally begins about his electric blanket, something that Esther Williams

also refers to at the very beginning of her autobiography. Here she talks

openly about her experiences with LSD and one of the things she describes was

when shortly after her experience she had dinner (!) with her parents and felt

she was able to see through them completely. It’s kind of scary as it’s the

exact same feeling I’ve had since first taking acid, as I so often feel like

Ray Milland in ‘The Man With The X-Ray Eyes’ in that I’m somehow able to see

right into the psyches of other people. When I’m having a discussion with

someone else, I always can tell the exact moment when that person gets hijacked

by his Ego (or by one of his subpersonalities or subs, as Bill Plotkin would

call it). If life were a comic book, you would see a red light flashing next to

their head, with thick steel doors being rolled down automatically, sealing

them off completely from what the Ego perceives as an attack. I don’t think

I’ve ever seen another movie that captures this moment to perfection as ‘My

Dinner With Andre’ in the moment Wally starts talking about the nice comfort

his electric blanket gives him and Andre points to the dangers such comfort can

bring. It is at precisely that moment that the subs of Wally start operating;

before that he may have been somewhat incredulous at some of the more

outlandish aspect of Andre’s stories, but either out of respect or decency he

doesn’t say much about it. When Andre touches the comfort of Wally’s blanket

though, things change considerably and he becomes incredibly defensive.

Unfortunately, this hijacking usually occurs with the person who’s being

hijacked being unconscious of it, which means these persons can’t really be

blamed for it as they are themselves entirely unconscious of it.

When

people are being hijacked by their subs, every kind of discussion becomes

virtually useless, as people are prohibited from receiving any information at

all – even though they themselves won’t see it this way. It was at this moment

of course that my own discussion become highly problematic and the girlfriend

of my friend became almost uncontrollable. It is yet another reason why

soulcentric development is preferable, as it is the only way to be truly open

to the world. Most people see themselves as really open-minded (ironically, my

old friend said exactly this at the beginning of the evening, even though some

time later he would prove the opposite), while they can only be as open-minded

as Ego will allow them – which is to say, not very open-minded at all. But as

the very concept of what open-mindedness is begins to mean something quite

different, depending on whether one is ego- or soulcentred, it also points to

the difficulty of true communication in this situation. It was true in my case,

but also in Andre’s: he understands everything Wally’s says (because he thinks

from a larger perspective) and in fact reacts to everything Wally brings to the

discussion with openness and understanding. Unfortunately, it’s not the other

way around, as Wally becomes hopelessly defensive and visibly frightened the

very moment Andre touches his core (the electric blanket). In the exact same

way as I could in my discussion, Andre can always think clearly, continue to

see the bigger picture and be generally open to the world around him. But just

as my discussion partners, at some point Wally became confused and crawled back

into his little private world of comfort and security, threatened as he feels

(or rather his Ego feels) by the radical implications of all that Andre stands

for. He can perhaps understand them on an intellectual level, but is quite

helpless to actually use any of it to transform his life. In the end, to Wally

everything is just dinner talk – empty and meaningless words to get through a

meal. Which of course is ironic, because at first he did claim he disliked

exactly that kind of empty communication. But true communication can only be

accomplished by true openness and true openness can only be found through

contact with Soul.

But

there is yet another argument why Andre’s position is much stronger and better

(if more risky and fraught with uncertainty), which is the one aspect the movie

fails the mention: the ecological component. I suppose Malle and his actors may

be forgiving as ecological awareness in 1981 had yet to make its big burst onto

the scene. Sometimes this is implicated as when Western civilization is blamed

as the main perpetrator of all the problems, which does link the movie with an

ecological book like ‘My Name is Chellis and I’m in Recovery of Western Civilization’.

But the crucial thing here is that living through the Soul is virtually

impossible without a thorough awareness of ecological issues as Soul is

directly infused with Spirit and Nature – which encompasses all things. Seeing

the big picture means not only being able to see the big picture in one’s own

personal life, but also that everybody is part of the even larger picture of

ecological and cosmological survival and well-being. It is exactly this

awareness that is the reward for all the personal ordeals one has to go through

when embarked on the soulcentric path, as it gives your life a sense of purpose

and direction within a much larger whole. Religious people will probably notice

that this purpose is quite similar to that which traditional religions have

always provided and which so many modern, unreligious people nowadays lack.

This lack of direction is also expressed by Wally when he says that everything

just happens by chance and it was in fact the crucial point my own discussion

escalated on, as my friends kept insisting on the very same thing. When I tried

to explain how this insistence on seeing life as nothing but an unrelated

string of coincidences made their live unnecessarily empty, as everyone should

be aware of the bigger picture every organism is part of, it was at this point

the girlfriend broke down in tears and left. Which was quite ironic as she was

active in an ecological political youth movement! Though both she and I felt a

deep rapport with ecological issues, this didn’t bring us closer together at

all and in fact only served to separate us. But this was entirely unnecessary:

it was nothing but an argument in which both sides wanted to convince the other

one of why their ideas were more valid. She obviously felt I was attacking her very

foundation (like Wally and his blanket), which was true enough, but she did the

same thing to me, which didn’t bother me at all as I was able to see the bigger

picture and can easily handle criticism. So had she lived in her Soul instead

of Ego, she could’ve seen my criticism was only meant to make her see certain

things she refused to see about herself and she could have noticed I was only criticizing

her position instead of her personally. Had she been able to make that

distinction, perhaps then she could’ve seen how the deep ecology movement is

based on two crucial aspects: diversity and harmony and how harmony will be

quite simply impossible as long as people refuse to see life as the circular, connected

web of influences that it really is. Now, as she was trapped within her Ego,

she just shut down completely, closing her mind off and rendering all that has

been said, like Wally, to meaningless dinner talk – yet all the while truly

believing herself to be open-minded.

Ecologist

Thomas Berry has coined the term of The Great Work, meaning that every human

should play his role in the work that should ultimately make the transformation

from a life-destroying society to a life-sustaining one possible. To perform

this task, everybody first has to find out what place he should occupy in this

world and what gifts are unique to him, in order to use these gifts not for

mere self-survival or self–advancement, but to adequately fulfill his part of

The Great Work. With ‘My Dinner With Andre’ Louis Malle and his two actors used

their special gifts to give us what may be the most important picture ever

made, as it points the way to a bright future. And I, in turn, have used my

gift to uncover some of the meanings of this particular film that otherwise could

have been lost on most, and in doing so I too have performed my little part of

The Great Work. It’s all really simple, see?

My Dinner with Andre (The Criterion Collection)

My Dinner with Andre (The Criterion Collection)